As

I have stated before, my relationship

with Goa and time spent interacting with and observing the Goans has made me

rethink and reinterpret my identity as a Canadian and what Canada is.

Over the

years, I have become progressively disenchanted with any display of

nationalism. During childhood, we are all made to learn the words to our

respective national anthem and sing it on cue, and participate in rituals

connected to holidays intended for patriotic celebration. Growing up in Canada,

we had to stand for the national anthem (O

Canada) in school every morning. As a music student, I and my fellow

concert band-mates were also made to play O

Canada for the school on many occasions. One Remembrance Day, in secondary

school, God Save the Queen was added

to the set list, effectively forcing us to pledge allegiance not only to the

idea of Canada but also to the monarchy that continues to enjoy the status of

our country’s official ruling power. And this is something that our government

asks of new Canadians. Yet some are availing of their legal right to

disavow

their oath to the Queen and her descendants.

The

monarchy is becoming increasingly irrelevant to us. And this is where I see

hope for this country. While we have just begun to take steps toward finally acknowledging the genocide and other heinous abuses

committed against the Indigenous peoples of what we call Canada, we have a very

long way to go.

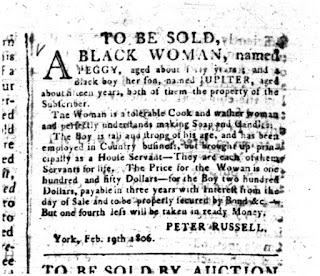

So much is not talked about in this country. For example, we have yet to truly acknowledge that slavery existed in

Canada.

But perhaps as more people immigrate to this country from every part of

the world, we can overcome the deeply racist conception of what it means to be

Canadian and welcome deeper political participation from people from various

backgrounds.

Some

will undoubtedly argue that we are already doing this, as the current Liberal Cabinet has two Indigenous

Canadians, an Afghan Canadian, and four Indo-Canadians. When the Cabinet was

formed in 2015, many Canadians agreed with the Prime Minister’s assertion that

he had chosen a Cabinet that “looks like

Canada”.

However, some Canadians, such as myself, were crying foul. Most glaringly,

there was not even one Black Canadian in the Cabinet. Numerous articles were

written on the subject (see, e.g., Rachel Décoste’s

article)

and debates were had on social media. These debates were intriguing in their

inconsistent logic. The Prime Minister had announced much before that his

Cabinet would comprise 50% men and 50% women. Not surprisingly, this prompted outcries

in print and television media that Trudeau was going to tamper with the

meritocracy!

Then when the induction occurred and the public saw the credentials of the

Cabinet Ministers, this rhetoric dissipated. But when those of us who saw

something was amiss with the representativeness of the Cabinet spoke out, we were accused of wanting to interfere

with the meritocracy! Some lazily argued that perhaps there just weren’t enough

Black, Asian, Arab, North African, Iranian, etc. Canadians in the Liberal

caucus for the Prime Minister to choose from. But a quick glance at the list of

elected Liberal MPs was all it took

to refute this argument. Further, as I pointed out then, all four Cabinet

Ministers of Indian ancestry are members of Canada’s Punjabi Sikh community; therefore,

they do not even reflect the diversity of Indo-Canadians.

Indeed,

I still maintain that the Cabinet reflects an ignorance (perhaps even a racist

notion) of what diversity means. This is not to say that the Cabinet Ministers

are unqualified for their positions; on the contrary. The problem in relation

to the discussion surrounding the Cabinet was all the self-congratulatory

back-slapping of the Liberal Party.

They boasted that this was the most diverse

Cabinet Canada had ever seen, when in fact, as Rachel Décoste pointed out, the

former Conservative Cabinet had actually set the bar for representing Canada’s multicultural

character.

Perhaps it was that Canadians were paying closer attention, given

Trudeau’s promise of change. Or perhaps it was that Trudeau’s team simply looked ‘more different’ to some people. Whatever the reason, such felicitation over

the composition of the Cabinet suggests that any person of colour can speak for

all people of colour—thinking that effectively others everyone who isn’t white.

Celebrating

the nomination of four Indo-Canadians to Cabinet whose ancestors can be traced

to the same part of the Indian subcontinent is interesting to me because it suggests

that there is some monolithic Indian identity. But as anyone who has ever lived

in South Asia knows, there is tremendous diversity among its inhabitants

(infinite languages and dialects, various religions and traditions within the

same religion, varying dietary habits, etc.). Such thinking is evident here

when someone born in Canada meets a Goan Catholic, for example, and is puzzled

as to why he or she has a Portuguese-sounding name. After all, this contradicts

the image of Indianness that has been framed in Canada (Aren’t all Indians either Hindu or Sikh and have surnames like Patel or

Singh?).

I

see parallels in this idea of a uniform Indianness when I’m in Goa too. It’s no

secret that there is heavy nationalism at play throughout India right now.

India is a beautiful and fascinating country; no two places are really alike.

This is both where the country’s strength lies and where it poses a challenge

to those who want to concisely define this landmass and the people who live on

it—which invariably takes the shape of a North Indian

identity.

Besides physically inhabiting the territory called ‘India’, what do the

citizens of India have in common? One can ask the same question about Canada.

Owing to its history, Canada seems to be in perpetual need of defining itself.

Similarly, since its annexation to India in 1961, Goa has been under pressure

to define itself in connection with the mainland. Undoubtedly, this pressure to self-define would

date back even further, but let’s deal with the present day for now.

The

complexities of Goa are such that I feel I’m still unravelling and only

starting to understand them—a decade-and-a-half after my first visit. While the

perspectives of the Goans are numerous, in everyday conversation about what is

happening and what the future should bring, the following three voices seem to ring

the clearest: (1) those who are caught up in nostalgia, (2) those who have a

strong sense of Indian nationalism, and (3) well-meaning types who lament the

loss of the natural environment and the character of the place they remember,

but who aren’t necessarily prepared to disrupt the status quo to stop this

process. I believe that none of these three perspectives is helpful. They all

overlook the greater problem that an external ideology is being imposed on Goa.

Indeed, I would argue that one of the issues holding Goa back is the desire for

a saviour—more specifically, an external saviour.

I see it in all three of the aforementioned

perspectives (e.g., the Portuguese vs. Congress–BJP vs. Arvind Kejriwal and a

Delhi-centred AAP). I rarely hear calls for Goans to unite and shape the future

of the state together. This may be the result of a long history of division

among the people (for a clear, succinct explanation of these divisions, see

e.g. Raghuraman S. Trichur’s book Refiguring

Goa: From Trading Post to Tourism Destination). Such a lack of unity can do

nothing but enable the ongoing destruction of the environment and physical and psychological

colonization.

I

had a heated discussion with an AAP volunteer in May, when we were both in

attendance at the same gathering in Panjim. She was singing Arvind Kejriwal’s

praises while criticizing the BJP’s Hindu nationalist ideology. I opined that

the lack of a strong local voice in AAP’s Goa wing was a problem, especially

since Kejriwal had recently addressed the crowd at the AAP rally in Panjim in

Hindi, using overtly Hindu nationalist language, including the phrase ‘Bharat mata ki jai’ (‘Victory to Mother

India’). Whether you do or do not take issue with this slogan, it is

significant for a politician from Delhi to come to Goa and say such a thing. Some

others mentioned that he hadn’t spoken in Konkani; this, I think, would be

unreasonable to expect, but it would not have been difficult for him to at

least greet the crowd in English. He chose

not to.

I asked her what reassurance she had that Kejriwal doesn’t espouse the

Hindutva ideology himself. The exuberant AAP volunteer told me that she just

knew in her heart that Kejriwal was trustworthy. She went on to ask me if I’m

Goan. When I told her that I am not, she lost interest in continuing the

conversation and walked away.

I’m

aware of the strange position I’m in as an outsider urging the Goans against

seeking deliverance from an outsider. My position is similar in the context of

my own country, as a white Canadian who is eager for the dismantling of the system

of whiteness that controls everything. In fact, my position as an insider–outsider

in Goa has not only helped me understand my privilege in Canada and as a

Canadian in the world but also the role that I can play in working towards

deconstructing this system as well as in challenging Canadians’ rigid ideas

about Indianness. So, similarly, my purpose in writing about Goa is in shining

a light on things as I see them from this particular position, without claiming

to have the answers.

Identity

is not just a project of the individual; belonging is also integral to this

formation. The myth of the uninhabited land is crucial to colonization; the

erasure of the locals and their identity allows the colonizer to use that land as he

sees fit. Thus, when we operate solely as individuals, this disconnects us

from each other and makes erasure possible. This has become clear to

me during my time in Goa, and I see similar workings in the exclusion of Black

Canadians and many others from power in Canada and from the Canadian identity.

What

does it mean to be Goan? If this question goes unanswered, it will cease to be

relevant, because another identity will be imposed on Goa. And as for Canada, I think many of us will agree that we still have work to do to figure out who we are.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.